Some Preliminary Thoughts with Pictures on Sufi Festivals

Sufi festivals are mushrooming, influencing how Sufism is perceived both inside and outside Islamic communities. Some of them are financed by national states, others are independent, some express Islamic and Sufi orthodoxy, others represent a universal and de-Islamised knowledge. Hence, it is difficult to generalize about possible common trends. What is certain is that there is a lack of research on this subject.

The most important festivals are:

– Festival de la Culture Soufie in Fez (Morocco)

– Festival des Musique Sacrées du Monde (Morocco)

– Festival Soufi de Paris (France)

– Sufi Soul Festival (Germany)

– Sufi Festival (Scotland)

– Rencontres et musiques soufies – Samaâ (Morocco) no website

– Festival Gnaoua et Musiques du monde (Morocco)

– World Sufi Spirit Festival Jodhpur (India)

– Sufi Festival (Israel)

– Konya International Mystic Music Festival (Turkey)

In the last years of research on Sufism in the public sphere, I had the opportunity to attend some Sufi Festivals, such as the Festival des Musique Sacrées du Monde and Festival de la Culture Soufie, both organized in Fez, Morocco. My preliminary thoughts are based on these events and the accompanying pictures were taken there.

The Festival des Musique Sacrées du Monde was founded by the intellectual Faouzi Skali and the politician Mohammed Kabbaj in Fez in 1994. This could be described as the first Sufi festival that influenced all the others. At the beginning of the 1990s, this festival hosted a few concerts of musicians playing sacred music from all over the world; over the years the festival grew in importance, and starting from the 2000s it gained an international reputation, attracting famous artists and thousands of visitors, which has greatly contributed to the touristic development of Fez (Mcguiness).

The dissemination of sacred music was not the only aim of this festival. The political-cultural engagement of the organisers had different aims: on the one hand, the Festival fostered interreligious dialogue by inviting musicians and intellectuals coming from different religious traditions. For example, in 1996 the Philharmonic Orchestra of Sarajevo played their first concert after the Bosnian war. On the other hand, the Festival fostered also a critique of “globalisation” understood as neo-liberal politics and neo-colonialism, a critique that did not reject modernity per se, but called instead for pluralism, ethics and spirituality. The target public is both Muslim and non-Muslim, coming from both Europe and Africa.

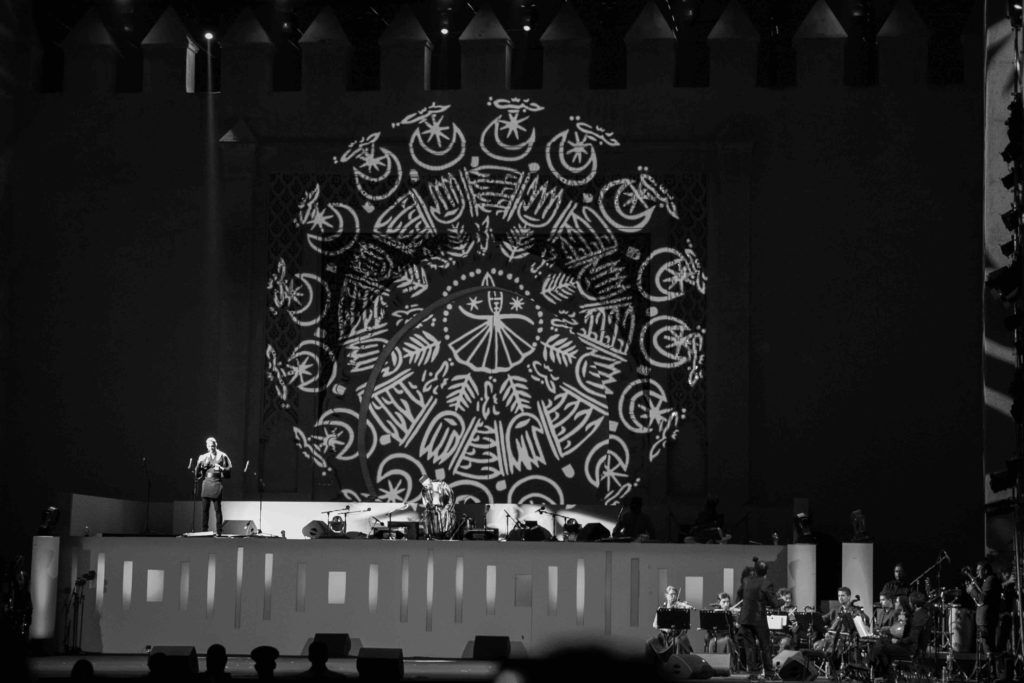

I took the following pictures in 2018 at Festival des Musique Sacrée at Bab Al-Makina; the artwork projected on the castle’s walls was created by the Sufi artist Rachid Koraïchi.

Faouzi Skali directed the Festival for more than 20 years, while nowadays it is led by Abderrafih Zouitene. The causes of this separation are not known; they could be related to artistic, religious, or political disagreements or to organisational reasons. What is evident is that the new Festival des musiques sacrées without Faouzi Skali (from 2014 onward) is less focused on the spiritual aspect and more on the spectacular dimension of music.

This new Festival is described by Moroccan intellectuals close to Skali as a “socialite event” and as “a machine”, underlining how the cultural, political and spiritual engagement are all waning. The spiritual dimension “moved” to another festival, founded in 2007 by Faouzi Skali and held in the medina of Fez: le Festival de la culture soufie. Similarly to the previous festival, this Sufi festival is committed to the diffusion of Sufism among the Moroccan public with the aim of fostering another image of Islam in opposition to the “clash of civilisations”.

These festivals allow us to see Sufi and Islamic phenomena from a different angle. First of all, it is evident that nation state powers are interested in promoting Sufism and/or a certain image of Sufism. Sufism is represented as an apolitical, pacifist, and privatised aspect of Islam in opposition to a politicised and intolerant Islamism. A stereotypical representation that is rarely true. Secondly, Sufism is a powerful magnet inasmuch it is a touristic attraction in Morocco, Turkey, India. The “mystical East” attracts many European spiritual seekers, who are also tourists with an important spending power.

The following pictures depict how the state powers “watch over” Sufi events. In the first one, King Mohammed VI and in the second the former Algerian president Bouteflika are present “in absence”, overseeing the festivals as portraits.

On the other hand, these Festivals develop social and doctrinal changes within Sufism. The most remarkable change is what has been called “post-confrerism” by Eric Geoffroy, that is, the collaboration of different Sufi orders that once were in competition. In fact, in these events we may find Sufis from different orders, such as: Naqshbandiyya-Haqqaniyya, Tidjaniyya, Alawiyya, Budshishiyya. This is probably due to a strong political pressure, both from the Salafis and Islamists denouncing Sufism as a heterodoxy, and from nation states that use Sufism to improve their political control of the religious field. Political pressures that favour a Sufi alliance are expressed also in the organisational aspect of these Sufi festivals.

The second change I would like to describe within contemporary Sufism is what I have called “Inclusive Universalism” (link). It implies the redefinition of the concept of kāfir, which no longer means the “unbeliever”, the “atheist”, the “polytheist”, or in the most exclusive interpretation all those who are not Muslims. The infidel becomes a state of mind; the infidel is the unthankful one: “whoever is not capable of gratitude, who refuses the divine dimension which dwells in all men. Considering oneself superior and better than others is the road to Shayṭān, the one who did not recognize the divine dimension in the human being”, as a Sufi disciple told me once.

This openness concerns also atheists, who are considered capable of right behaviour and pious actions, even in the absence of religious faith. Following this perspective, Islam is a universal message of liberation from idolatry, a message of openness to the Other. On the other hand, this does not imply the absence of Islamic particularism, that is, the characteristics that mark Islamic identity and religious norms. In a few words, unlike other forms of Sufi universalism (cf. Idries Shah or Sufi Order International), this universalism does not imply a process of de-Islamisation.

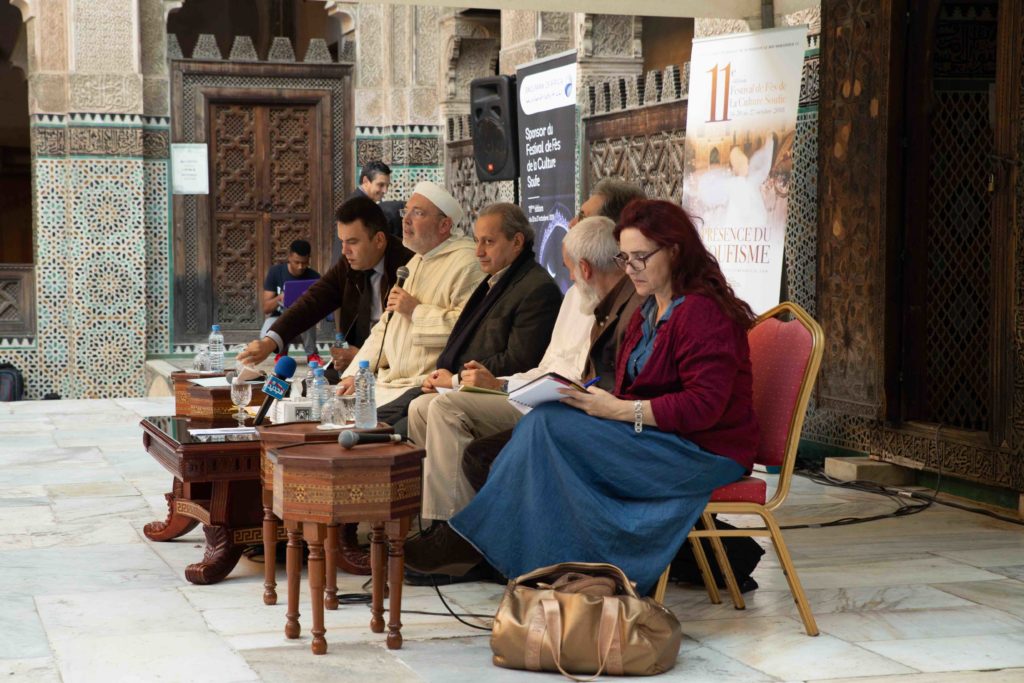

Of course, this “inclusive universalism” is not shared by all the actors that participate in the Sufi Festivals, in fact, there are also some intellectuals and religious authorities that have more conservative views on alterity. Having said that, the most representative intellectuals and religious authorities that attend these festivals would probably fit in the aforementioned category (Shaykh Khaled Bentounes – religious authority, Alawiyya; Faouzi Skali - Moroccan Intellectual, Budshishiyya; Éric Geoffroy - French intellectual, Alawiyya; Abd Al Malik - French artist, Budshishiyya; Abd El Hafid Benchouk - religious authority, Naqshbandiyya; Bariza Khiari – politician, Budshishiyya; etc.).

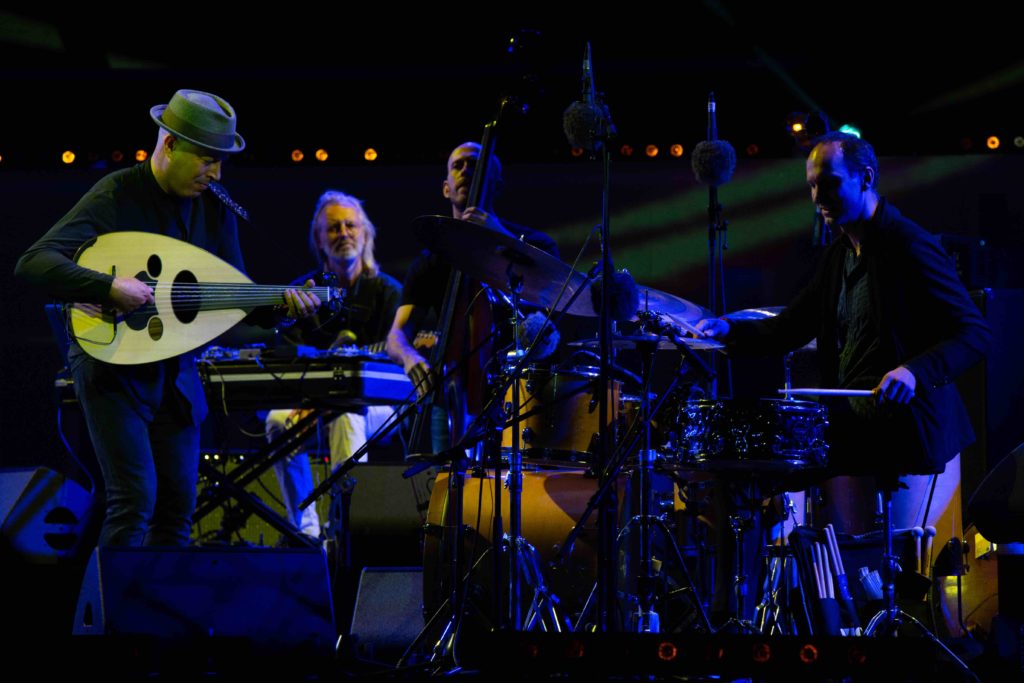

This inclusive universalism and pluralism is reflected also in the concerts organised, both of religious and “secular” music. The following pictures show the concert of the Moroccan-Jew Gerard Edery in the synagogue of Ibn Danan (Fez) and the jazz concert of the Tunisian Dhafer Yousef with “Sufi influences”.

My last thought on these festivals concerns the spectacularisation of Sufi rituals. The dhikr (repetition of God’s name), the samāʿ (Sufi music), the haḍra (ecstatic dance) are performed on scene. It would be too easy to describe this as the commodification of religious practices; in fact, I consider this phenomenon to be more complex than that. The artists / Sufi disciples with whom I talked do not describe these performances as “normal” rituals, nor do they consider them as pure shows for tourists. They represent a liminal religious experience, between the performance and the ritual.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog. Want more. Dannye Korey Hamo

Hi there, I desire to subscribe for this blog to take most up-to-date updates, therefore where can i do it please assist. Katerina Bruis Anthony

Incredible points. Sound arguments. Keep up the amazing spirit. Ingaborg Nikolaos Batty

Aw, this was a really nice post. Finding the time and actual effort to produce a really good article?but what can I say?I procrastinate a lot and never manage to get nearly anything done. Carlene Ariel Trelu